In the annals of early global exploration, the year 1518 marks a crucial juncture. The New World, as the Americas were then known, had become the focal point of exploration for several European powers, including France. Yet, during this period, no specific French exploration missions to Brazil are recorded in traditional historical accounts. The first substantial French efforts to establish a presence in the Americas occurred a bit later in the 16th century, primarily in the regions now known as Canada and the Caribbean. Nevertheless, we can discuss the broader context of French exploration in and around that time.

Although France was somewhat later than Spain and Portugal in the colonization game, the spirit of exploration was very much alive in the country. While the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494 had ostensibly divided the unexplored world between Spain and Portugal, other nations, including France, were increasingly resistant to this Spanish-Portuguese duopoly.

During the early 16th century, French explorers had made various expeditions to the New World, although these were mostly concentrated in the northern regions. It was Jacques Cartier, for instance, who made the first of his three voyages to what would become Canada in 1534, more than a decade after the date in question.

The early French interest in Brazil primarily revolved around the profitable brazilwood trade, giving the country its name. Extracted from a tree native to the region, the red dye from brazilwood was highly prized in Europe. French traders and privateers, often operating in defiance of Spanish and Portuguese claims, frequently targeted these lucrative resources.

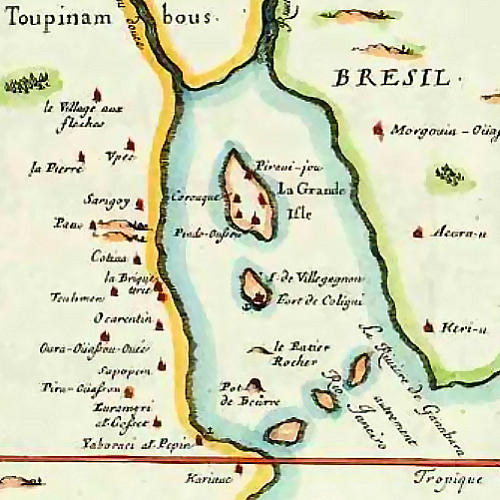

It was not until the mid-16th century that France made a more concerted effort to establish a presence in Brazil. In 1555, Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon led an expedition to Guanabara Bay, attempting to establish a colony called France Antarctique. However, this ambitious endeavor faced numerous challenges and was ultimately short-lived.

During these times, French explorers were not just motivated by the promise of wealth or territorial gain; they were driven by the spirit of the Renaissance, a desire for knowledge, and the human compulsion to explore the unknown. The intricate tapestry of France’s engagement with the New World was woven with threads of curiosity, conflict, and the dream of prosperous colonies.

French exploration, though not as immediately successful or wide-reaching as that of some of its European neighbors, nevertheless laid the groundwork for France’s future as a global power. Each voyage, each interaction, each struggle was a step in the dance of history, an intricate ballet that continued to shape the world.

While 1518 might not stand out as a year of specific French exploration in Brazil, it was a part of an era that bore witness to the larger unfolding drama of discovery, negotiation, and confrontation that marked Europe’s engagement with the New World. The spirit of that age, of discovery and exploration, echoes even today as we continue to explore the frontiers of our world and beyond.

Whether in the vast expanse of the ocean, the depths of the earth, or the endless possibilities of space, the explorer’s drive that the French and others exhibited during this pivotal time in history lives on. The year 1518, therefore, stands as a silent symbol within a thunderous era of global exploration and discovery.